Another Planet and Include Another Kind of Being Easy City of Another Planet

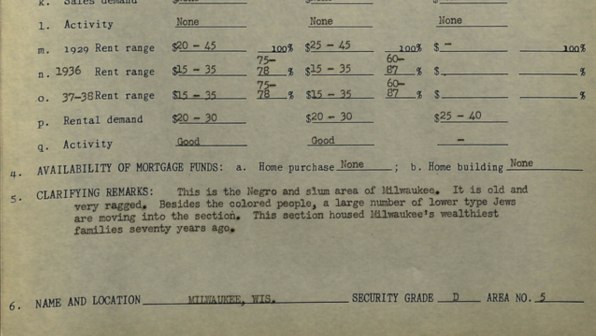

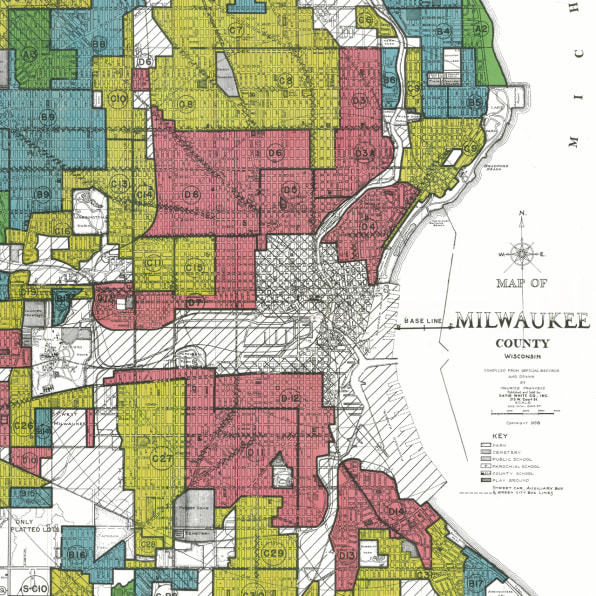

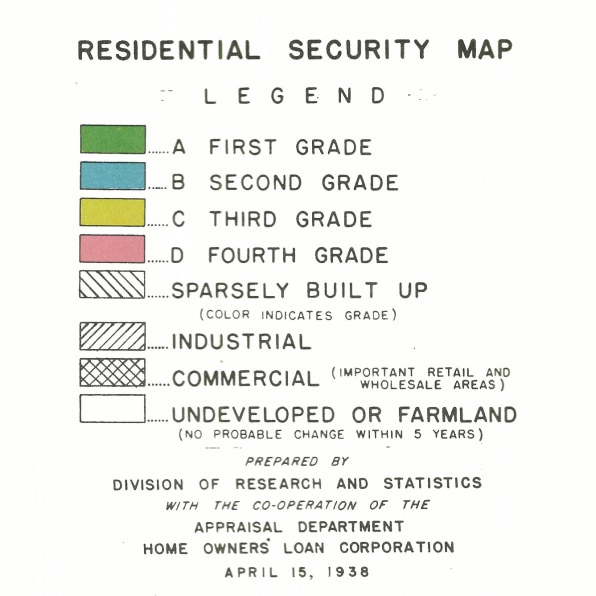

On a 1938 map of Milwaukee created for a federal agency, assessors shaded 19 areas red, marking them as a "hazardous" risk for home loans or insurance. A set of forms accompanying the map evaluated each neighborhood. Some were deemed a risk because of problems like polluted water or a lack of modern sewers. But each form also assessed race and ethnicity.

One "Negro and slum area," the form says, home to "laborers and ne'er-do-wells," also housed a growing number of "lower type Jews." (One Russia-born Jewish woman who grew up in the area in the early 1900s was Golda Meir, the future prime minister of Israel.) Another red neighborhood had an "infiltration" of Polish and German immigrants, and another form noted a "predominating foreign element" as a "detrimental influence" along with smoke and odors from nearby factories.

The so-called redlining maps were used in cities throughout the U.S., part of blatantly racist New Deal policies: As the government tried to rebuild the housing market after the Great Depression and prevent foreclosures, an agency called the Home Owners' Loan Corporation asked local realtors and assessors to give neighborhoods in more than 200 cities grades of "best," "desirable," "declining," or "hazardous," quantifying the number of black and foreign-born people living there. The lower the grade, the less likely someone could get a loan from a bank to buy a house; in a redlined neighborhood, it could be nearly impossible.

Historians disagree about how the HOLC maps were used, though there is evidence that they were used by private lenders and also may have influenced Federal Housing Administration maps. If the FHA didn't approve a loan, that could effectively kill it. This type of discrimination was outlawed in 1968 with the Fair Housing Act, though in practice, it still sometimes occurs.

On a weekend in February, a group of mostly white Milwaukeeans boarded a school bus to take a tour through some of the former redlined neighborhoods. "We grew up in this city, and hopefully we can provide some real personal information around redlining," says Joaquin Altoro, one of the organizers of the tour.

Altoro, whose day job is as vice president of commercial banking at a local bank, is the grandchild of a man who came to Milwaukee from Mexico in the early 1900s to work at a tannery. As Altoro and co-organizer Adam Carr researched the history of redlining in Milwaukee, they discovered the notes for the neighborhood where Altoro's grandfather bought his first house. "Mexicans are encroaching in the Northeast," it said.

"The words that were used were crazy," he says. "I'm standing here at the house where my grandfather came, looking at the map and the notes, and I promise you, this is a direct correlation to my grandfather being one of the first Mexicans."

The tour stopped at places like Columbia Savings and Loan, the first black-owned bank in the city, which helped black residents get loans that weren't available elsewhere, and talked about the history of the city's black neighborhoods. At another stop, the group met with a black developer who is turning a vacant building into a startup incubator.

The Milwaukee neighborhoods that were marked red still bear impacts from the government's 20th-century policies. Haymarket, one neighborhood in a redlined district, has a median household income of $17,778 today (the median household income for all of Milwaukee is $58,029) and a higher unemployment rate than the rest of the city. One recent study found that nationally, areas that were redlined still had more segregation and lower home values and homeownership as of this decade than neighborhoods with better grades, and redlining maps were directly responsible for some of this gap. At the same time, because of a growing population and demand for housing in cities like Milwaukee, some of the same neighborhoods that people of color were once forced into are now gentrifying, forcing residents out.

"In Milwaukee right now, we're going through a renaissance," says Altoro. "The neighborhoods outside of downtown are starting to be redeveloped, and we're dealing with affordability." Near his grandfather's former home, there are now cocktail bars and loft apartments. "I asked the question, 'I'm just curious, what do you think if I were to have a long-time Hispanic family fill out these notes today, who would they call those that are 'encroaching?' It's all relative. It's a hard conversation."

Similar stories are playing out in other cities, and in a handful of other places, residents are also organizing tours to share the history. In March, biking and walking tours in Seattle looked at the city's historically black Central District (despite the name, the district wasn't particularly convenient to downtown and was less desirable).

"This is where the black community was essentially forced into," says Leonard Garfield, executive director of the Museum of History and Industry, one of the organizers of the tours. "As you crossed from one side of the red line to the other, you'd go from neighborhoods that had large homes on large lots to homes that were much more modest, much smaller lots, and generally just not the public infrastructure that you'd find in other places. There was neither the private wealth nor the public investment in this neighborhood."

A current exhibit at the museum shows the art of an African-American photographer named Al Smith, who documented midcentury life in the Central District. "Constrictions and hostility and segregation created the community," Garfield says. "But what [Smith] recorded was the joy and the strength that was in that community despite that oppression." Ray Charles and Quincy Jones grew up in the neighborhood. The local jazz scene influenced Jimi Hendrix. Now, as Seattle deals with a housing shortage, the neighborhood's black population is shrinking and some of the culture is ebbing away.

In Portland, Oregon, the Fair Housing Council of Oregon hosts bus tours that explore local discrimination and segregation. When Oregon became a state in 1859, it explicitly outlawed black people from living there. If you were black, it was illegal to move to Oregon until 1926. Today, Portland is still the whitest large city in the U.S. The tour shows places like Vanport City, where shipyard workers (including thousands of black workers) lived in temporary housing near the Columbia River until a flood destroyed their homes and killed some residents. After the flood, black families struggled to find new housing. Most of the city's African-American population lived in the Albina neighborhood, described in a 1930s redlining map as having an "infiltration of subversive races." Urban renewal projects in the area later razed houses for a highway and a hospital. Now, as Portland struggles with quickly housing prices, Albina has gentrified.

But Portland is also trying new policy: prospective first-time homebuyers who were displaced from their old neighborhood because of old urban renewal policies can apply for down payment assistance from the city's housing bureau. The program also gives preference for new rent-subsidized apartments to people who previously lived in areas of the city affected by urban renewal. People whose homes were seized by eminent domain get priority. People who can show that their parent or grandparent also lived in the neighborhood go to the top of list.

The program is helping a small number of those who were displaced–just 65 people will get assistance buying homes. It also can only begin to address some of the long-term effects of former government policy and can't replicate community that has been lost; some former residents may not necessarily feel at home in a neighborhood that is now "a gentrified, upper-middle-class white neighborhood with brewpubs, coffee shops, and high-end restaurants," says Allan Lazo, executive director of the Oregon Fair Housing Council.

Black families who couldn't buy homes in the 1940s or 1950s couldn't grow equity to share with the next generation, creating a massive wealth gap between races that still persists. Other government policies beyond redlining also had significant impacts: another New Deal policy helped build new suburbs to meet housing demand, but then required that the deeds for each house would limit black families from ever purchasing the property in the future (these were outlawed by the Fair Housing Act in 1968). People of color are still more likely to be denied a home loan than white people today, after controlling for income and other factors, according to a report from the Center for Investigative Reporting.

In the tour in Milwaukee, "We didn't have a call for action at the end," says Altoro. "There was nothing activist about this at all . . . disparities, and race, and racism, segregation, these aren't easy topics. So for somebody to take a Saturday morning and go hear about this stuff, I give you real credit for that. What you do about it? I don't know."

But a tour's ability to show a hidden part of urban history could be a step to support for better policy. "Knowing that history can help both policymakers and community members have a have a framework or a lens that can inform what policy should look like from a community's perspective," says Lazo, of the Oregon Fair Housing Council. On his organization's sold-out tours, which happen from 20 to 30 times between April and October, 50 people at a time pack on the bus. "It's amazing the number of people who . . . are from Oregon and don't know this history, or don't understand it." The Portland tour has inspired similar tours in places like Hartford, Connecticut.

If your own city doesn't offer one, you can try taking a self-guided tour yourself: This website shows the original redlining maps, and racist comments, for 150 cities.

Source: https://www.fastcompany.com/40556164/a-new-kind-of-city-tour-shows-the-history-of-racist-housing-policy

0 Response to "Another Planet and Include Another Kind of Being Easy City of Another Planet"

Postar um comentário